Escrito por William F. Jasper

|

The Great Seal of the United States

|

|

Países que receberam ajuda do Plano Marshall

|

«[...] é no campo da política externa que se levanta agora um aspecto delicado. Com intermitências, continua reunida em Paris a conferência dos dezasseis, para organizar e administrar o auxílio económico e financeiro dos Estados Unidos. Caeiro da Matta, em sucessivas viagens a Paris, avista-se sobretudo com Bevin e Bidault [político francês, que emergira da resistência, e que é agora ministro dos Estrangeiros], e ambos mostram a melhor disposição perante o governo português. A este, apresentam-se dois problemas: a atitude a tomar em face do pedido de Madrid para ser acrescentada a Espanha aos "dezasseis" e a posição a assumir para com o próprio Plano Marshall. Em Conselho de Ministros, de 27 de Janeiro de 1948, Salazar submete as questões ao gabinete. Não há dificuldade quanto ao primeiro ponto: na medida do possível e, sem prejuízo dos seus interesses, Portugal apoiará a Espanha. Mas suscita-se debate quanto ao segundo problema. Deve Portugal aceitar empréstimos, créditos e mesmo dádivas dos Estados Unidos para acorrer às necessidades mais prementes e para fomento em geral? Alguns ministros, mais directamente ligados ao fomento, inclinar-se-iam para aceitar a aplicação do Plano Marshall ao país. Salazar segue, no entanto, um ponto de vista diverso. Tem o chefe do governo suspeitas dos objectivos americanos: receia que a penetração dos Estados Unidos no sentido da Europa constitua, mais do que um auxílio a esta, um desígnio imperial de Washington; teme que uma preponderância económica e financeira americana no Ocidente Europeu seja apenas uma forma de acesso às posições europeias no continente africano; e apavora-o a ideia de que a vulnerabilidade das estruturas portuguesas possa tornar estas presa fácil de um credor poderoso, que para mais se julga predestinado ao exercício da hegemonia global. Estes aspectos, expostos pelo chefe do governo ao Conselho de Ministros, levam o gabinete a uma decisão negativa. Portugal comunica aos demais quinze que, em princípio, dispensa largos créditos americanos: prefere pagar com exportações portuguesas o que houver de adquirir: e apenas deseja, além de uma ou outra ajuda limitada, que sejam progressivamente eliminadas as restrições impostas pelos outros países e que nestes se abram mercados aos produtos portugueses. E pelo que respeita à Espanha os delegados de Lisboa deparam com uma recusa: no Ocidente Europeu, os regimes de matiz socialista não querem admitir aquela, sem embargo de reconhecerem a sua importância no conjunto económico.

[...] Regressado aos Estados Unidos, Dwight Eisenhower apresenta a sua candidatura à Presidência, em nome do partido republicano; é eleito; e sucede a Harry Truman. No Departamento de Estado, Dean Acheson é substituído por John Foster Dulles. Tem repercussões no mundo o resultado da eleição: que política será a de Eisenhower? Em França, acentua-se a instabilidade governamental, e desta resulta uma oscilação constante da atitude de Paris. Schumann abandona os Negócios Estrangeiros, e regressa Georges Bidault; e de novo estão em causa o papel da França, na NATO, e as relações com a nova Alemanha de Konrad Adenauer. Neste particular, o debate político em França trava-se sobre a questão de manter um exército francês autónomo, ou de o europeizar numa união da Europa Ocidental, ou na estrutura da NATO; e ainda sobre o estatuto da Alemanha, que ressurge como Estado federal, e a cooperação desta com o Ocidente. São tradicionais os receios da França perante um ressurgimento do poderio germânico; restabelecer este, todavia, parece indispensável para resistir ao expansionismo soviético; há que procurar, desta forma, o melhor enquadramento para uma Alemanha remilitarizada; e Londres e Washington, com a anuência de Bonn, inclinam-se para a entrada da nova República Federal no quadro do Pacto do Atlântico. Por seu lado os Estados Unidos, sob a orientação de Dulles, reforçam uma política de alianças para além da NATO, e destinada a conter a penetração russa: as Filipinas, a Austrália, a Nova Zelândia, a Tailândia, o Paquistão, a França e o Reino Unido dão o seu aval a essa política; e em paralelo com a NATO, é firmada a SEATO [South East Asia Treaty Organization].

Em Lisboa, Salazar, sempre apaixonado pela situação do mundo, não deixa de se sentir preocupado, e mesmo perplexo. Como a encara neste momento? Escreve para Bruxelas, a Eduardo Leitão: "Noto na vida internacional uma pausa, de um lado provocada por ninguém saber quais serão e até onde irão as divergências no respeitante aos negócios do mundo entre a administração de Eisenhower e a de Truman, por outro pela mutação no governo da França que se encontra em face de uma opinião pouco disposta a aceitar o exército europeu, ou talvez mais precisamente a dissolução do exército francês no exército europeu". E quanto a ideias federalistas? "A meu ver", diz Salazar, "as ideias federalistas que parece terem sido tão do agrado de franceses e italianos e não sei se belgas e holandeses, apesar do impulso que por todas as formas lhes dão os americanos, encontram dificuldades de execução e até poucas simpatias em muitos meios, convencidos de que se trata menos de um problema europeu do que de arranjar maneira de resolver dificuldades da política francesa". Em nada disto tem Portugal que estar envolvido, mas "o caso é sobretudo desagradável porque estes vai-vens da política europeia fazem perder tempo na organização de forças e no estreitamento da cooperação económica, militar, cultural e política que, sem federação ou com federação, é possível e necessário estabelecer e reafirmar".

Estas preocupações pela defesa do Ocidente não são exclusivas de Salazar. São partilhadas por homens eminentes, da política e das letras, em muitos países do Ocidente. Há pouco fora Henri Massis, que viera desabafar junto de Salazar a sua ansiedade; e agora é a Gustave Thibon, da mesma linha ideológica de Massis e de Gabriel Marcel, que Salazar recebe, e interroga sobre a situação francesa, e de quem escuta iguais desabafos. E são também homens da política: é André de Staercke, muito ligado a Paul Spaak, que em cartas e visitas não esconde o seu pessimismo; é Van Acker, primeiro-ministro belga; é Paul Van Zeeland, que continua ministro dos Estrangeiros da Bélgica; são outros ainda. E justamente Van Zeeland acaba de convocar Eduardo Leitão e de lhe pedir para consultar o chefe do governo português sobre a conjuntura mundial, e em particular os negócios da Europa e as ideias em curso quanto ao futuro desta. Leitão tudo transmite para Lisboa, e Salazar responde à consulta de Van Zeeland no dia seguinte ao da morte de Estaline. Traça um quadro inicial: "As coisas aparecem-nos assim: os Estados Unidos, pela simplicidade do seu espírito e ligeireza das suas opiniões, não vêem para a Europa outra solução política que não seja a unidade através da federação; a França, que se nos afigura um país cansado de lutar e a quem a plena independência parece pesar, adopta a ideia como a maneira mais fácil de evitar o rearmamento alemão isolado e amanhã potencialmente hostil; as nações que se agrupam em volta da França parecem convencidas, embora por motivos diversos, de que aquele é o melhor caminho de salvar a Europa e talvez o único de assegurar o apoio americano, em potência militar ou em dólares". Desdobra depois o seu pensamento: há apenas duas realidades, que são uma ideologia americana e uma política francesa: mas a viabilidade de executar a ideia, o ambiente político e moral, os problemas económicos, estão em plano secundário, embora sejam o essencial. Por ideologia americana, entenda-se uma ideia de partido político no governo; por política francesa entenda-se a de uma fracção dos políticos franceses, porque a França, "se anseia por não ter de bater-se, também procura não ser mandada por outros"; e quanto ao receio de perda do auxílio americano, "penso que esse receio não tem razão de ser, porque a Europa é tão necessária à América como esta à subsistência da liberdade europeia". Mas "é sobre tão frágeis fundamentos que se anda a construir a federação da Europa". E essa federação é possível? No domínio lógico, é. Apenas há duas maneiras, no entanto, de a conseguir: por acto de força de um federador ou por lenta evolução que pode levar séculos. Não existe um federador: "se a Rússia puder, talvez ela o faça nos países danubianos sob a sua égide; se Hitler tem ganho a guerra, era possível que obrigasse a Europa a federar-se sob a hegemonia alemã; e pelos frutos e demoras da evolução não se quer esperar". E que pode resultar de uma federação? Resultam o abandono de terras, arrumação ou concentração de indústrias, deslocação de populações, desequilíbrios económicos, perdas de interesses e capitais: são sofrimentos sem conta, alterações profundas nas maneiras de viver e de pensar: "mas retoma-se a vida em novas bases, e no futuro, num futuro largo, pode até ser melhor para todos os que então existirem". Isto pode fazer-se pela força; não o podem fazer os políticos, ao menos de um dia para o outro, contra interesses inconciliáveis e os sentimentos das populações. Porque a verdade é que a Europa nasceu de um certo modo e tem um certo carácter; a sua diversidade, se é fraqueza, é também fonte da sua radiação universal; tem nações tão antigas que o seu nacionalismo se confunde com o instinto de propriedade; e é duvidoso que por combinações ou tratados se possa erigir o Estado Europeu. E, se se constituísse, esse Estado Europeu seria por muito tempo destituído de coesão e força efectiva: "o momento óptimo para o ataque russo, se a Rússia pensasse em atacar o Ocidente, era exactamente o da constituição do Estado Federal Europeu". Essa federação, a fazer-se, far-se-ia sob a égide republicana: comportaria três grandes repúblicas (França, Alemanha, Itália) e três pequenas monarquias (Bélgica, Holanda, Luxemburgo): a força das primeiras, a dificuldade de escolha de uma dinastia comum, o desejo dos americanos, imporiam a solução republicana: e os três pequenos países teriam de se desfazer das suas instituições. Depois, há o problema colonial. Itália e Alemanha foram despojadas de tudo; os domínios ultramarinos serão integrados na federação, que herdará as colónias belgas e francesas; os que nada têm a perder são os que têm tudo a ganhar; mas a Bélgica e a França não pertencem a esse grupo. Deste modo, uma federação europeia suscitará mais problemas do que resolve; constituiria por muito tempo uma construção política e economicamente frágil; por cima de sacrifícios e sofrimentos a impor às gerações actuais, a Federação poderá dispor de mais espaço, racionalizar a produção, conseguir com os territórios ultramarinos uma maior base económica para o conjunto. Acontece que, pela sua força e capacidade, será a Alemanha quem conduzirá a federação para todos os seus destinos. "Para isto, talvez não valesse a pena ter feito a guerra". E a Inglaterra? No território europeu, a Inglaterra funciona já como um estado federal; no mundo, é a cabeça de uma associação de Estados. Se a Inglaterra tomar na Europa o compromisso de um esforço total, será a perda da chefia da comunidade; e os vários Estados que compõem esta, privados daquele ponto de apoio, procurarão outros pólos de atracção. Parece desassisado que, em nome de uma unidade hipotética, se desfaça ou corra perigo de desaparecer uma outra unidade, já existente e de real valor.

|

Bandeira da NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization).

|

Neste quadro, que posição convém a Portugal? Independentemente da aliança antiga, e considerando apenas o jogo das forças mundiais que emergem, importa a Portugal uma Inglaterra forte e independente: "quem nos dera que possa continuar a ser um factor de equilíbrio entre os Estados Unidos e uma federação europeia em que a Alemanha seja o elemento preponderante". No mais, e "se posso ser intérprete do sentimento do povo português, devo afirmar que é tão entranhado o seu amor à independência e aos territórios ultramarinos, como parte relevante e essencial da sua história, que a ideia da federação, com prejuízo de uma e de outros, lhe repugna absolutamente". Nos dissídios da Europa, raras vezes Portugal interveio; e sempre com dano de outros interesses mais altos. Se agora se compromete no Pacto do Atlântico, e para caso de ataque pelo imperialismo russo, "é que há a compreensão nítida de que esse imperialismo traz consigo os elementos destrutivos da nossa mesma razão de ser"; e por isso evitar aquele ataque "é condição necessária ao prosseguimento da nossa missão no mundo". Da Europa, interessam a Portugal a paz, o génio e espírito da civilização cristã, e mais nada; e Angola e Moçambique interessam bem mais. Felizmente, são de tal relevo os Pirenéus que abrigam a Península de uma absorção ou decisiva influência; a Espanha, com as suas ligações à América Central e do Sul decerto vê mais futuro no conjunto hispano-americano do que numa federação europeia. Do debate em torno do problema, a Portugal somente interessa não ser embaraçado no seu caminho; e por isso se tem abstido de intervir em discussões públicas ou de pertencer a alguns organismos, como o Conselho da Europa e outros. Portugal sabe que não pode influir na evolução das ideias e dos acontecimentos: "mas não devemos esquivar-nos a dizer com inteira lealdade o que pensamos acerca de umas e dos outros".

[...] E em 27 de Março de 1957 [Salazar] acolhe o general americano Norstad, novo comandante supremo da organização militar do Pacto do Atlântico. Salazar agrada-se de Norstad: é longa a conversa: e este diz ao chefe do governo que considera fundamentais para a defesa do Atlântico e do Ocidente as posições portuguesas em África. Pela política interna, Salazar sente cada vez mais viva a sua repugnância, e esta é quase invencível. Diz aos seus íntimos: "é lama, lama da mais sórdida". Volta-se para os acontecimentos internacionais, com uma atenção pormenorizada e um pensamento concentrado. Preocupam-no agora novos factos. Vê que em torno de Portugal se adensa um mundo diferente, que alicia as imaginações, os espíritos, as vontades. Muitos tomam-no como gestação de uma nova época, de uma nova vida, de uma nova civilização. Para além das aparências, contudo, Salazar vê nos sucessos internacionais o definhamento de uns impérios, e a emergência de outros, e as novas construções políticas e os novos conceitos ideológicos, são os instrumentos dessa deslocação dos grandes centros do poder. Naquele mês de Março de 1957 produz-se um facto capital: é assinado o Tratado de Roma, de que são membros a França, Alemanha, Itália, Bélgica, Holanda e Luxemburgo. Estabelece a Comunidade Económica Europeia, ou Mercado Comum, e prevê a redução progressiva de tarifas pautais entre os signatários, a abertura das fronteiras ao capital e ao trabalho, a criação de instituições supranacionais. Por entre as disposições de natureza económica, financeira ou administrativa, o tratado é eminentemente político: que atitude deve Portugal assumir para defesa dos seus interesses? Do tratado surgirá uma nova Europa? E qual? Por outro lado, nessa mesma Europa, os grandes povos parecem entregues à luta entre si próprios, presos de ideologias que os dividem. Na sequência de Suez, está traumatizada a Inglaterra, sem embargo da solidez das suas instituições políticas; está traumatizada a França, e a sua IV República desagrega-se de crise em crise; e perde terreno na Itália a democracia-cristã. Salazar sente-se apreensivo, e está pessimista. Para além da Europa, agravam-se os conflitos. Todo o mundo árabe está em efervescência, e na Argélia enfrenta a França um levantamento, que não consegue dominar, e que é ajudado pela Tunísia, por Marrocos, pelo bloco-soviético, por alguns círculos políticos norte-americanos. E por toda a África Negra francesa alastram as influências ideológicas que fermentam a instabilidade; e o escol local, educado em França, arvora o estandarte do nacionalismo. Paris lança a lei-quadro, que define um estatuto de autonomia interna numa estrutura comunitária. Processo diverso, de um desenvolvimento constitucional que conduz a resultados idênticos, adopta a Inglaterra na África britânica: e a Costa do Ouro, com o nome de Ghana, surge para a independência, sob Nkrumah, que considera seu mandato providencial libertar a África ao sul do Sara, desde Dacar ao Cabo e a Madagáscar. E nos demais continentes lavra a inquietação, a ansiedade, o conflito latente ou aberto, a guerra civil disfarçada. No desarmamento, e sem embargo de sucessivas reuniões internacionais, não é dado um passo; a guerra fria, oficialmente abandonada, mantém-se sob a coexistência pacífica; e os novos messianismos imperiais alastram pelo mundo. No contexto das Nações Unidas, na lógica política da contracção europeia, definha a força ocidental; com esta, e para surpresa de Washington, sofre uma erosão a influência dos Estados Unidos, que encontram dificuldade crescente em manipular a ONU; e produz-se um esforço dos blocos afro-asiático e soviético. Muitos vêem nos factos a eficácia da Organização de Nova Iorque. Salazar vê nos factos a alteração do equilíbrio de poderes no mundo, que a ONU reflecte. E quando a União Soviética faz explodir a sua bomba de hidrogénio, num avanço tecnológico que frisa com o dos Estados Unidos, não se modifica por essa circunstância, de súbito, a posição: mas agrava-se, em desfavor do Ocidente, o desequilíbrio psicológico e político. E acentua-se a tendência para levantar no seio da ONU problemas de raiz nacional: a educação, a política económica, a política comercial, os direitos humanos; passa-se ao debate sobre o acesso aos mercados, à distribuição de matérias-primas e seus preços; e discutem-se conflitos internos, problemas de soberania, questões bilaterais. De tudo, são de confirmar as conclusões já tiradas: o anticolonialismo tem por alvo o Ocidente; atacada, a Europa concentra-se sobre si própria; nessa contracção, tem a tendência para acreditar na supranacionalidade como defesa; os problemas nacionais são internacionalizados, com enfraquecimento das soberanias; e essa internacionalização, estimulada e explorada pelos novos impérios, conduz a um intervencionismo mundial praticado pelas forças em conflito. Perante esta sociedade que desponta, cabe a pergunta: é definitiva ou efémera? Está-se à beira de uma nova época e de uma nova arrumação da humanidade? Ou enfrenta-se uma vicissitude mais ou menos longa mas passageira? Num caso e noutro, há que tomar decisões diferentes, e todas são vitais para o futuro. Que fazer de Goa, que tanto significa na história de Portugal? E de Timor, que tantos esforços consumiu durante a guerra? E de Macau, uma jóia de família? E da África, de tão grande valor e importância? Salazar desabafa com homens de confiança: "Estou na ponte de comando mas em torno só vejo nevoeiro cerrado".

[...] Três gerações se sucederam já: a que fizera o 28 de Maio, trinta e dois anos atrás; a dos homens que, tendo na altura entre trinta e quarenta anos e perante instituições e sistemas completamente desacreditados, aderiram com fé ao Estado Novo; e a dos que, muito jovens na época, cresceram no regime e por este foram absorvidos. Mas agora chegou à superfície e quer intervir na vida colectiva uma nova geração para quem o ponto de partida das instituições, e do regime e seus princípios, está esquecido: para estes, recordações dos tempos antigos e a comparação com os actuais são desprovidas de significado; o contacto com ideias que supõem novas e modernas leva à tentação da aventura, da mudança pela mudança; e julgando que não podem percorrer novos caminhos e satisfazer as suas ambições políticas no quadro do regime, há que derrubar este, ainda que não haja projecto assente para o futuro e sejam quais forem as consequências para interesses nacionais, já encarados à luz daquelas ideias, e a curto prazo. "Depois se verá", dizia mestre Aquilino. Por detrás de tudo, há a massa do povo português. Ao cabo de mais de trinta anos do mesmo regime, os portugueses viram subir o seu nível de vida, o país caminhou; e, dentro dos seus recursos e sem embaraço de faltas e desvios, a sociedade portuguesa ampliou os seus horizontes, incorporou as novas técnicas, avançou no plano material. Sociologicamente, houve uma circulação de elites. Não são rígidas as classes do sistema, nem estão fechadas, e comportam o ingresso de novos valores, e o seu acesso até aos mais altos escalões. Salazar viera do nada; e do nada viera a esmagadora maioria dos seus ministros. No sector privado, muitos homens também surgidos do nada atingem, por trabalho e iniciativa, os mais elevados postos na economia, na indústria, na banca, nas profissões liberais, na vida social. Alarga-se a classe média, e a esta ascende toda uma massa que vem dos assalariados e do proletariado. Generalizam-se, sobretudo nas cidades, alguns sinais exteriores do progresso, do conforto, do desafogo económico. Não aumenta velozmente o poder de compra, os salários são modestos; mantém-se o valor da moeda, todavia, e são firmes os preços; e o crescimento da sociedade, se é lento, é estável também. Mas o sistema, ao mesmo tempo que é sociologicamente aberto, não cria mecanismos de defesa ideológica: conduz uma sociedade que lhe aproveita as vantagens sem lhe absorver a mística nem lhe suportar os inconvenientes. Quase de repente, fica perante um quadro de novos princípios e de novos valores, importados sob pressão exterior. É antes de mais o internacionalismo. De novo, como em épocas passadas, a humanidade é uma só: os homens são todos irmãos, as fronteiras entre países são um artifício sem fundamento, as soberanias das nações são um entrave à felicidade colectiva. Estas convicções conduzem directamente ao mito dos organismos internacionais, a que se atribui pureza de objectivos, e isenção de procedimento, e cujas decisões, por espelharem a consciência da humanidade, devem ser respeitadas como imperativos categóricos. Daqui o apego ao pacifismo; a paz é valor supremo, superior ao direito, à justiça, à verdade; e não se aceita como lícita a defesa em face de uma violência ou de um ataque que, se invocarem os novos princípios em curso, são criadores da sua própria legitimidade. São por isso de condenar as estruturas militares, os gastos com a defesa. E no plano religioso surge o progressismo no seio da Igreja Católica: esta é acusada de autoritarismo, de imobilismo, de apego a um passado que não se conforma com o progresso e a ciência, de comprometimento com César: e procura-se transferir para uma sociedade, que se transforma em messiânica, os atributos de Cristo. Da Cúria de Roma, o progressismo é disseminado em larga parte do mundo católico; e crescem os seus adeptos na Cúria de Lisboa, na Hierarquia, em sectores da Acção Católica, e entre membros do clero secular. Está-se à beira de uma nova civilização, de um mundo novo e sem raízes; e a Igreja tem de lhe corresponder. Por outro lado, há é toda uma concepção sociológica que deve comandar a política: é a sociedade permissiva, é a sociedade de abundância, é a sociedade de consumo. São opressivas as peias morais, e a consciência de cada homem é o juiz último dos seus actos; e apenas é livre o homem pletórico, e sem passado. Há a certeza da felicidade pelo progresso contínuo; a obsessão do crescimento constante; a ânsia do futuro; e os conceitos de diálogo, de contestação, de abolição de hierarquias entram na vida e nos hábitos correntes. Surgem as crises de camadas sociais: a alta burguesia está receosa da sua própria função; a classe média descrê dos seus princípios; a classe operária reivindica uma economia independente dos recursos; e os homens não devem estar ao serviço de nada, salvo de si próprios. É cega a fé na ciência e na técnica para resolverem problemas sociais ou morais. Negam-se as hierarquias por destruírem a igualdade. Qualquer constrangimento é entrave à liberdade. E para debater todo o acervo de novas ideias multiplicam-se em Lisboa, e pelo país, os cursos, as conferências, os colóquios, os seminários, os centros de estudo e cultura, e são discutidas as ciências sociais, as ciências económicas, as ciências políticas, as novas disciplinas, as novas técnicas, os novos temas do presente e do futuro que apaixonam os homens. Influenciável pela última verdade, que toma como definitiva; volúvel, e crédulo, de entusiasmo tão súbito como fugaz; facilmente deslumbrado pelo que é alheio - o povo português sente um peso, uma fadiga, um desejo de mudar; a habitualidade de Salazar é havida como um travão. Contrapõem-se a estes sentimentos o receio de aventuras, a defesa dos bens alcançados, a suspeita perante o desconhecido: então, a habitualidade de Salazar constitui uma garantia. Até quando? E se há de mudar, mais tarde ou mais cedo, não é preferível mudar imediatamente? Ou será melhor fazê-lo o mais tarde possível?».

Franco Nogueira («Salazar. IV, O Ataque, 1945-1958»).

«[...] a 25 de Setembro de 1961, Kennedy aproveitara a XVI Assembleia-Geral das Nações Unidas para, na qualidade de líder do Ocidente, condicionar a agenda política mundial. Ora, aí afirmara a sua crença no futuro das Nações Unidas, propusera o desarmamento e o fim dos testes nucleares, como ainda reconhecera a ameaça comunista sobre Berlim e a Indochina. No lance, concluíra dramaticamente: «Juntos salvaremos o nosso planeta ou juntos pereceremos nas suas chamas».

|

John Foster Dulles

|

|

Oliveira Salazar

|

Deste modo, eis como a Administração Kennedy estaria preparando, passo a passo, a entrega da soberania dos Estados Unidos para a Organização das Nações Unidas. Nessa medida, o desarmamento americano, particularmente considerado, teria, por contrapartida, a consolidação das forças militares da ONU até ao ponto em que nenhuma nação do planeta pudesse contrariar o respectivo monopólio militar. E a comprová-lo, encontra-se igualmente o discurso do Presidente Kennedy na ONU, a 20 de Setembro de 1963, no qual "insistiu na criação de uma força militar das Nações Unidas".

A par disso, intensificava-se um ataque selectivo à presença multissecular de Portugal em África, onde, aliás, a política americana não era de todo estranha ao jogo dos russos. Vários eram, pois, os objectivos de uma tal política, nomeadamente o aumento da dependência dos portugueses relativamente ao exterior, a montagem de uma rede de informações sob a capa do Peace Corps, quando não mesmo a possibilidade de grupos e movimentos terroristas poderem solicitar a intervenção das forças da ONU. Senão, veja-se:

"Conquistar 'os corações e as mentes' do Terceiro Mundo era uma prioridade de Kennedy. O Presidente transpôs para a luta personalizada com Khruschev o ardor competitivo da sua educação familiar e a sua obsessão de “ser o primeiro”. Perante a multiplicidade de crises em África e na Ásia, e face à popularidade do comunismo, tratava-se de vencer os soviéticos no próprio jogo em que eram mestres: a subversão de países estrangeiros. Na primeira reunião do Conselho de Segurança Nacional, em 1 de Fevereiro, Kennedy ordenou a MacNamara que desse relevo às doutrinas de contra-subversão no programa do Pentágono. Formou-se um Special Group para as questões de insurgency, que incluía Robert Kennedy e Maxwell Taylor, Chefe do Estado-Maior General das Forças Armadas, e surgiram os Green Barets, uma força de elite que atingiu rapidamente 12 000 membros. A mobilização foi geral: mais de 100 000 diplomatas americanos e mais de 7000 estrangeiros receberam cursos de contra-subversão durante a Administração Kennedy. Este novo espírito traduziu-se também na criação do Peace Corps, uma espécie de liga de missionários do idealismo americano, onde se alistaram muitos jovens para acções de humanitarismo em países do Terceiro Mundo".

Por aqui se pode, de alguma forma, entrever como Washington, a par de Moscovo, Praga e Pequim, ajudara a implementar o terrorismo na África portuguesa por acção e intermédio do comunismo. Além disso, os Estados Unidos entendiam limitar o problema português a uma mera questão de lucros e perdas, pelo que assim mostravam não compreender que Angola, Moçambique e outras partes constitutivas da Nação Portuguesa, estavam essencialmente ligadas por laços de solidariedade histórica e espiritual. Daí que Oliveira Salazar, que tivera sempre presente que as independências se regem pelas leis da evolução histórica condicionadas pelo desenvolvimento económico, social e político dos territórios e respectivas populações, procurasse acentuar, perante o inferno das Nações Unidas, no que consistia o ideal português da interpenetração de culturas, simultaneamente caracterizada pelo princípio da não-discriminação racial e pela igualdade do homem perante Deus e a lei.

Por consequência, Salazar operava na base da unidade da Nação portuguesa, tida à época como princípio constitucional, o que desde logo implicava a independência do todo na interdependência dos componentes ou partes constitutivas dessa mesma Nação. Depois, não deixa de ser paradoxal o facto de, já numa época em que se procuravam estabelecer grandes blocos políticos e económicos, ter preponderado, no Ocidente, uma atitude crítica e, muitas vezes, condenatória com vista à destruição do bloco português. E, portanto, tudo isso numa época em que o comunismo internacional estava táctica e estrategicamente apostado em destruir os valores ocidentais em África, designadamente em Angola».

Miguel Bruno Duarte («Winston Churchill e Oliveira Salazar»).

«Abater fronteiras! Riscá-las dos mapas! Apagá-las das almas».

António Quadros («Franco-Atirador»).

«[...] é óbvio que o ataque à existência multirracial e pluricontinental de Portugal constituíra, no fundo, uma etapa indispensável para o predomínio de uma Europa inimiga das soberanias nacionais, consoante, aliás, convém ao governo mundial que aí se avizinha. Ora, sobre o governo mundial, já o jornalista americano Constantine Brown, em conversa com Franco Nogueira, afirmara, em 16 de Maio de 1962, o seguinte:

a) O Presidente Kennedy era um "fraco sem personalidade", dominado por um grupo "composto por uma meia dúzia de pessoas, como os Srs. Rostow, Schlesinger, Bundy, sendo o primeiro o mais influente";

|

| JFK |

b) Esse grupo tinha "como ideal supremo: 1) apaziguar a Rússia por todos os meios; 2) sacrificar, se necessário, toda a Europa Ocidental; 3) abolir as soberanias, incluindo a dos Estados Unidos; 4) criar 'um só mundo' governado pelas Nações Unidas";

c) Para o efeito, o Governo Kennedy já estava, em relação à Europa Ocidental, a tentar "destruir os Governos do chanceler Adenauer, do presidente De Gaulle, do presidente Salazar e do general Franco".

Bastam, pois, estas três primeiras alíneas, a que o jornalista americano aditara outras mais directa ou indirectamente relacionadas com o governo mundial, para irmos ao encontro de quem, em entrevista conduzida por Fernando Pereira e publicada no Novo Século a 1 de Agosto de 1982, dissera que António de Spínola, comportando-se como um completo ignorante político, destruíra o futuro dos portugueses...».

Miguel Bruno Duarte («Illuminati»).

«The emerging European superstate, now moving forward under the EU, is the result of a deliberate scheme put into motion many years ago by powerful planners and plotters.

Few Americans realize how closely linked are the onrushing developments transforming Europe into a regional superstate and the campaign underway here to create a similar hemispheric entity for the Western Hemisphere. Europeans have only recently begun awakening to the fact that the decades-old politico-economic convergence process behind the European Union (EU) seriously threatens their freedom. Belatedly, they have started to react.

The “European project” is a euphemism for the plan to gradually enlarge the EU until it includes all European nations (including Russia and Turkey) while increasing EU jurisdiction over more and more areas now reserved to the nation-states. On the immediate horizon is the merger artists’ proposed European Constitution, completed on June 18, and designed to lock Europe into the EU trap. If carried to completion, as envisioned by the EU founders, this project would utterly destroy the national sovereignty and independence of its member states. It would destroy all representative government in Europe and concentrate absolute legislative, executive and judicial power in the hands of an administrative elite.

Obviously, it would have been far better for the peoples of Europe never to have ventured into the trap in the first place. And therein lies the lesson for Americans. Very few Europeans saw or understood the warning signs and cleverly disguised snares during the period of the 1940s through the ’80s, as myriad Lilliputian threads were being transformed into steel cables. It has only been in the past decade or so that the enormity and severity of the trap have begun to be apparent. We will have no excuse if we follow the same path.

Yet, that is what we are doing, via NAFTA and the proposed CAFTA (Central American Free Trade Agreement) and FTAA (Free Trade Area of the Americas). The same world-government-promoting organizations that were propelling the “European project” - the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), the British Royal Institute of International Affairs (RIIA) and the international Bilderberg Group (BG) - are the major forces working behind the scenes to merge North and South America into a centralized regional government patterned after the EU. In fact, our previous article “A NAFTA/FTAA Rogues’ Gallery” (see our April 5 issue and stoptheftaa.org) included a profile of an American Insider who played a key role in establishing the Common Market/EU more than half a century ago, and is playing a central role in the current NAFTA/CAFTA/FTAA deception: David Rockefeller.

David Rockefeller, was 30 years old at the end of World War II. He had graduated from Harvard in 1936, then gone on to study economics at the Fabian Socialist Society’s London School of Economics and the University of Chicago. Following the war, he was appointed secretary of the CFR “study group” that put together what became known as the Marshall Plan. He would later become chairman of the CFR, a founding member of the Bilderbergers (where he is now the “senior statesman”), and founder of the Trilateral Commission, the Council of the Americas, the Forum of the Americas and the Americas Society - all leading engines in the drive for hemispheric convergence.

Joseph Retinger, one of the major architects of the Common Market/EU, noted in his diary:

In November 1946, I had a very long talk with Mr. Averell Harriman, American Ambassador in London.... Averell Harriman was my sponsor and arranged my visit [to the U.S.].... At the time (the end of 1946) I found in America a unanimous approval for our ideas among financiers, businessmen and politicians. Mr. Leffingwell, senior partner in J.P. Morgan’s, Nelson and David Rockefeller, Alfred Sloan, Chairman of the Dodge Motor Company … George Franklin, and especially my old friend, Adolf Berle Jr., were all in favor, and Berle agreed to lead the American Section. John Foster Dulles also agreed to help us.... Later on, whenever we needed any assistance for the European Movement, Dulles was among those in America who helped us most.

All of the individuals mentioned above were leading CFR Insiders. They and their CFR colleagues and European counterparts were the real movers behind the “movement” that was portrayed in the CFR-dominated U.S. media as a popular, grass-roots effort to unite Europe. In the past few years, official European and U.S. documents have been released showing that the organized European Movement was almost entirely bankrolled with U.S. funds, courtesy of the (unaware) American taxpayers, much of it illegally funneled through CIA fronts. While these revelations have received some coverage in Europe, they have been almost totally ignored by the American press.

The following profiles provide important information largely unknown (and difficult to uncover) by the general public regarding some of the key individuals and events involved in the founding period of what is known today as the EU. What becomes strikingly obvious, once the facts are laid on the table, is that the EU engineers have employed massive deception, lies and propaganda to foist a hidden, criminal agenda on the unsuspecting peoples of Europe and America. That hidden agenda is now moving into a new phase that aims at replicating the EU program in this hemisphere. By understanding the tactics that have been used by these merger forces in Europe, Americans will be better equipped to understand, oppose and expose those same forces pushing the same hidden agenda here today.

Sir Winston Churchill (1874-1965). As Britain’s prime minister during World War II, Winston Churchill was promoted to Homeric stature by the major media. His irascible, dominating personality and famous wartime orations made him Europe’s towering political personality in the immediate postwar era. Churchill started his political career as a Conservative Member of Parliament in 1900, before going over to the Liberal Party in 1904. He served in various Cabinet positions in Liberal Governments before switching back to the Conservative Party in 1925.

Despite his Conservative Party label, he flirted openly with anarchists and Fabian Socialists, expressed admiration for the early fascist regimes of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, and was an ardent advocate of the Welfare State. Above all, Churchill was a zealous internationalist. In 1930, his essay entitled “The United States of Europe” was published in the Saturday Evening Post as an early volley in support of European supra-nationalism. During the war, in a March 22, 1943 broadcast, he called for creating a Council of Europe to govern “under a world institution embodying or representing the United Nations.”

On September 19, 1946, Churchill made his famous speech in Zurich, in which he declared: “We must build a kind of United States of Europe.” He then helped found the United Europe Movement (UEM), a British organization, along with his son-in-law Duncan Sandys and Lord Layton, a leader in the Royal Institute of International Affairs. Churchill was the chairman, with Sandys operating as executive chairman. At the 1948 Hague Congress of Europe, Churchill, as “President of Honor,” delivered the opening address, in the presence of Princess (later Queen) Juliana and Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands.

|

Bandeira do federalismo europeu adoptada em 1948. Ver aqui

|

In October 1948, the UEM joined with other continental organizations to form the European Movement and Churchill was named one of the Presidents of Honor, along with France’s Leon Blum, Belgium’s Paul-Henri Spaak and Italy’s Alcide De Gasperi. Churchill was a major figure at subsequent conferences and the leading proponent of a European Army. His prominence in the Conservative Party not only helped immensely to undermine Tory opposition to the surrender of British sovereignty, but also helped provide a more moderate image for the European Movement, which was dominated by socialists. He remained active in the movement throughout his life, and one of the three European Parliament buildings is named in his honor.

Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands (1911- [2004]). As founder and titular head of the ultimate Insiders club, the Bilderberg Group, His Royal Highness Prince Bernhard enjoyed, for many years, a degree of global influence matched by very few individuals, royal or otherwise. German by birth, Bernhard is the elder son of Prince Bernhard von Lippe and Baroness Armgard von Sierstorpff-Cramm. In the 1930s, as Hitler rose to power, Bernhard’s younger brother publicly supported the Nazis, while Bernhard himself trained as a fighter pilot and was commissioned an officer in the German Reiter SS Corps. He then went on to become an officer in I.G. Farben, the huge German corporation that was an industrial centerpiece of Hitler’s regime.

Dutch-German relations were already very strained when, on January 7, 1937, Bernhard married Princess Juliana, the future Queen of the Netherlands. Bernhard’s private meeting with Hitler in Berlin shortly before that and his entertaining of SS officers at the Dutch royal palace did not endear him to the Dutch people. When the Germans invaded Holland, Bernhard fled to England and joined the Royal Air Force, but was still viewed with suspicion by the Dutch and the Allied Command. After the war, American and British Insiders began his public rehabilitation. He was appointed to the boards of literally hundreds of corporations and foundations, where he became familiar with the heads of business, finance, philanthropy, government and academia. In 1961 he founded the World Wildlife Fund, one of the world’s largest and wealthiest environmentalist groups, which gave him tremendous political influence among environmental NGOs and at the UN. In 1952, he was approached by Joseph Retinger (see below) with the proposal to start a select group that could hold private meetings on the future of Europe and Atlantic relations. Thus the Bilderberg Group (BG) was born, so named because its first meeting, in 1954, was held at the Hotel Bilderberg in Holland.

Around a hundred of the world’s top movers and shakers are invited to the annual BG meetings, which are always held under a strict veil of secrecy and very tight security. From the beginning, BG attendance has been top-heavy with Insiders from the CFR and RIIA, and, especially in its early years, with those who were exercising power over Europe’s reconstruction under the Marshall Plan.

Attendees at the founding Bilderberg meeting, for example, included: David Rockefeller, global banker and later chairman of the CFR; Dean Rusk, president of the Rockefeller Foundation and later U.S. Secretary of State; Joseph E. Johnson, president of the Carnegie Endowment; C.D. Jackson, head of Time, Inc.; Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, former head of the OSS, precursor to the CIA; and Lord Dennis Healey, Labor Party leftist and later British Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Although the European Movement was already launched by the time the BG conferences began, the Bilderbergers have played a key role in every advance of European supranationalism, from the European Coal and Steel Community to the Common Market to the EU. Ernst H. van der Beugel, honorary secretary-general of the BG and vice president of the Dutch affiliate of the CFR, matter-of-factly explains in his 1966 book, From Marshall Aid to Atlantic Partnership, how his Bilderberg-CFR friends in the U.S. government utilized their offices and U.S. funding to strong-arm or bribe European leaders who resisted the European Movement.

Joseph Retinger (1888-1960). Virtually unknown to the European and American public, Joseph Retinger is, nonetheless, recognized and praised by EU Insiders as one of the key founding fathers of the European Movement.

|

Joseph Retinger à direita

|

He is one of those mysterious figures in history who - without political office or social or economic standing - operates behind the scenes and exercises an influence vastly disproportionate to his apparent circumstances. A penniless, Polish socialist and stateless exile without any visible means of support, Retinger bounced back and forth between Europe, Mexico and the U.S. during the 1920s and 30s. During World War II and the postwar period, he was constantly traveling between England, Russia, the Middle East and Central Europe. He was an emissary of and adviser to President Calles of Mexico, as well as confidant to, interpreter for and representative of General Sikorski, leader of the Polish government in exile in England.

Among the world movers and shakers whom Retinger counted as friends and benefactors were U.S. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, ambassador and business tycoon Averell Harriman, British newspaper publisher and Astor family heir David Astor, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and New Deal Brain Trust adviser Adolf Berle. He also exerted an extraordinary influence over Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands; it was Retinger who recruited the prince to launch the secretive, super-elite Bilderberg Group. In Prince Bernhard’s foreword to John Pomian’s authorized biography, Joseph Retinger: Memoirs of an Eminence Grise, Bernhard writes that with regard to the Bilderbergers, Retinger “was, in point of fact, the prime mover.”

A lecture by Retinger to the Royal Institute of International Affairs at Chatham House on May 7, 1946 is credited with jump-starting the organized European Movement, of which Retinger was made the first secretary-general. Retinger served as the backstage director and gatekeeper of the critically important Congress of Europe in May 1948 at The Hague. He was primarily responsible for drawing up the list of the 800 dignitaries attending the Congress, which included 18 ex-prime ministers and 28 ex-foreign ministers. No doubt, due in large measure to his influence and careful selection, he could write of the Congress in his diary: “Everybody realized that insistence on national independence and the preservation of national sovereignty were outdated.” Retinger also wrote that when Italian Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi was hesitant about joining the movement, he won him over by quipping, “Come, let us now join forces and conspire together.” Whether spoken in jest or not, Retinger proved himself the arch-conspirator, successfully shepherding the treasonous unification scheme from one stage to the next.

The Congress gave birth to the Council of Europe, which held its first session in Strasbourg in August of 1949. “The Council of Europe was conceived,” wrote Pomian, Retinger’s longtime companion and biographer, “as an institutional first step which might in time lead to some kind of supranational Government of Europe.” However, Retinger and his company of one-worlders did not advertise this objective. In fact, as the peoples of Europe became more suspicious of appeals for “pooling sovereignty” in a centralized European State, the leaders of the European Movement denied that this was their objective.

Jean Monnet (1888-1979). Jean Omar Gabriel Monnet, son of a brandy merchant from Cognac, made a small fortune shipping war materiel during World War I and then began his political ascent at the Versailles Peace Conference. At Versailles, the Frenchman connected with British members of the RIIA and their American counterparts who would return to the U.S. to form the Council on Foreign Relations. In 1919, at the age of 31, he was named secretary-general of the newly formed League of Nations.

Monnet, a lifelong socialist, was, along with Joseph Retinger, one of the top behind-the-scenes managers of the 1948 Congress of Europe at The Hague. At the same time, 1947-48, Monnet was working closely with U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall to design what came to be known as the “Marshall Plan,” the scheme that pumped over ten billion American dollars into the political coffers of Monnet and his fellow one-world socialists in Europe.

|

Jean Monnet

|

|

Países fundadores da Comunidade Europeia do Carvão e do Aço (CECA): Bélgica, França, Itália, Luxemburgo, Holanda e Alemanha Ocidental.

|

|

Walter Hallstein, Jean Monnet e Konrad Adenauer

|

As head of France’s General Planning Commission, Monnet was the real author of what came to be known as the 1950 “Schuman Plan,” to create the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), forerunner of the Common Market. Merry and Serge Bromberger write in their admiring biography of Monnet that the ECSC scheme was “an idea of revolutionary daring” aimed at the gradual creation of a “superstate.” They note that Monnet and his fellow Insiders planned for national governments (often led by their fellow one-world agents) to make “a whole series of concessions in regard to their sovereign rights until, having been finally stripped, they committed hara-kiri by accepting the merger.”

Once the ECSC was established, Monnet was named the first president of this powerful cartel that controlled the production of energy and steel for much of continental Europe. In 1955 he founded the Action Committee for a United States of Europe, one of the major forces pushing and directing European convergence. Monnet’s Action Committee brain trust drew up the 1957 Treaty of Rome, which created the European Common Market. And it was Monnet, operating through U.S. diplomatic machinery, who notified American internationalists whenever pressure was needed from the U.S. government to put European politicians in line behind the merger betrayal.

Robert Schuman (1886-1963). One of the EU’s “Founding Fathers,” Robert Schuman was born in Luxembourg but grew up in France. In 1919 he was first elected as a deputy to the French Parliament, where he served for twenty years. Following World War II, Schuman served as France’s prime minister, foreign minister and finance minister. From 1955-1961 he was president of the European Movement, and from 1958-1960 president of the European Parliament in Strasbourg.

As previously mentioned, the European Movement and its many affiliates were almost completely financed with funds provided by the CIA, the Marshall Plan, and private Insider sources such as the Ford, Rockefeller and Carnegie foundations. Once Jean Monnet’s Action Committee had drawn up the plan for the European Coal and Steel Community, he approached Schuman to sponsor it. Schuman did, and the ECSC was launched as the “Schuman Plan” for Europe. The Robert Schuman University in Strasbourg, the Robert Schuman Center in Florence, the Robert Schuman Institute in Budapest, the Robert Schuman Journalism Award and other monuments attest to the valuable services this European globalist performed for those who seek to submerge Europe in a regional superstate, as one building block in a one-world government.

Paul-Henri Spaak (1899-1972). Known as “Mr. Socialist,” Paul-Henri Spaak was elected to parliament as a member of Belgium’s socialist Labour Party in 1932 and later served several times as Belgium’s foreign minister and four times as prime minister. He presided over the Consultative Assembly of the Council of Europe and the General Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community in the early days of both institutions.

In 1945, he gained international prominence as the first elected chairman of the UN General Assembly. In 1948, he accompanied Winston Churchill, Duncan Sandys, and Joseph Retinger on a trip to America to secure U.S. funding for the European Movement. Their effort resulted in the formation of the American Committee for a United Europe, headed by CFR leaders William Donovan (former OSS director) and Allen Dulles (future CIA director).

In 1955 Spaak chaired the preparatory committee of the Messina Conference of European leaders, where he was principal author of what came to be known as the “Spaak Report,” credited with setting the stage for the Monnet-Schuman Plan and the Common Market. In 1956 he was chosen as secretary-general of NATO. Spaak’s influence was instrumental in the choice of Brussels as the headquarters for both NATO and the EU».

William F. Jasper («Rogues' Gallery of EU Founders», in The New American, 12 July 2004).

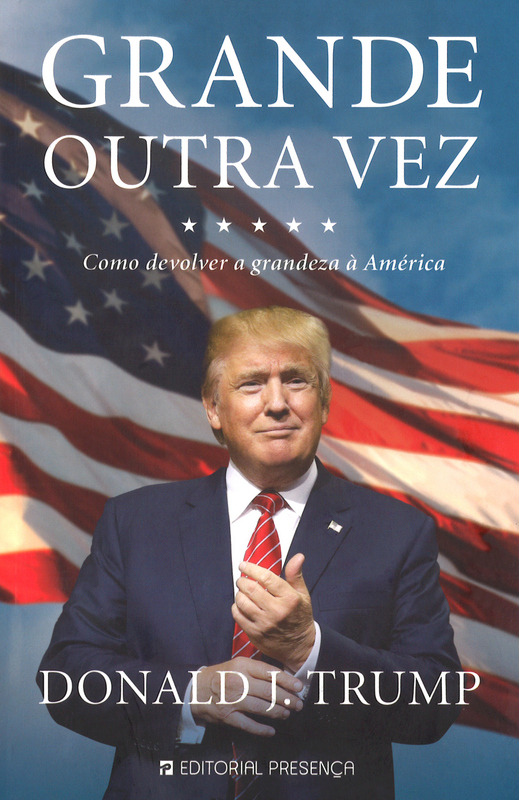

«Na luta pelas audiências, todos os programas tentam fazer notícia. O problema é que não estão a fazer bem o seu trabalho. Não estão interessados em informar o público. Pelo contrário, querem é jogar o seu joguinho do "apanhei-te". Tal como já disse, alguns dos média políticos são muito desonestos. Não querem saber de publicar a verdade, não querem repetir as minhas afirmações na íntegra e não querem dar-se ao trabalho de explicar o que eu queria dizer. Eles sabem perfeitamente o que eu disse, sabem o que quis dizer e editam as minhas palavras ou interpretam-nas de modo a conferir-lhes um significado diferente.

Fui recordado desse comportamento quando anunciei a minha candidatura à presidência no dia 16 de Junho em Nova Iorque. Falei demoradamente sobre os problemas que estamos a enfrentar: a imigração ilegal, o subemprego, um produto interno bruto a diminuir, um arsenal nuclear envelhecido e o terrorismo islâmico. Falei sobre todos esses temas. Em que é que a comunicação social se focou? Concentraram-se no facto de eu ter dito que o México nos enviava os seus piores habitantes através da nossa fronteira meridional. "Enviam-nos pessoas que têm muitos problemas", foi o que eu disse. "E trazem-nos estes problemas até nós".

A próxima coisa que se ouviu foi que Trump dissera que todos os imigrantes eram criminosos. Não foi isso que eu disse de todo, mas isso deu aos meios de comunicação social uma história muito melhor. Proporcionou-lhes algumas manchetes. O que eu disse foi que, entre os imigrantes que vêm do México, havia pessoas muito más, alguns desses elementos são violadores, outros são passadores de droga, outros ainda vêm para cá para viverem à custa do sistema, e que era melhor tomarmos medidas duras e imediatas para fechar as nossas fronteiras aos "ilegais".

As pessoas que me conhecem sabem que eu nunca insultaria os hispânicos nem qualquer grupo de pessoas. Já fiz negócios com muitos hispânicos. Vivi em Nova Iorque toda a minha vida. Sei o quão maravilhosa a cultura latina consegue ser. Tenho consciência do quanto contribuem para o nosso país. Tenho dado emprego a muitos bons trabalhadores hispânicos ao longo dos anos. Tenho um grande respeito pelos hispânicos, mas não foi isso que os média relataram.

Isto foi o que os meios de comunicação social relataram: TRUMP CHAMA CRIMINOSOS A TODOS OS IMIGRANTES e TRUMP CHAMA VIOLADORES A TODOS OS MEXICANOS!

Totalmente ridículo.

Um dos problemas que os média políticos têm comigo é o facto de eu não ter medo nenhum deles. Há outros que praticamente lhes imploram pela atenção deles. Eu não. As pessoas reagem bem às minhas ideias. Estes tipos de média vendem mais revistas quando o meu rosto está na capa ou quando lhes trago uma audiência muito, mas muito maior do que o habitual a um dos seus programas. E o mais engraçado é que parece que a melhor forma que têm para conseguirem a atenção é criticando-me.

Contudo, o povo americano está a começar a compreender isso. Finalmente perceberam que muitos dos média políticos não tentam dar às pessoas uma representação justa dos temas importantes. Pelo contrário, tentam manipular as pessoas - e as eleições - em prol dos candidatos que querem ver eleitos. Estas empresas de comunicação social pertencem a bilionários. Essas pessoas inteligentes sabem bem quais os candidatos que serão melhores para elas e arranjam uma forma de apoiar a pessoa que querem.

[...] Quando anunciei a minha candidatura, falei durante quase uma hora, cobrindo quase todos os desafios que enfrentamos. Porém, o tema que obteve mais atenção foi o meu foco sobre a política de imigração. Ou, para ser mais correcto, a nossa falta de uma política de imigração coerente. Fui bastante duro com os imigrantes ilegais e muita gente não gostou disso. Eu disse que muitos países estão a despejar os seus piores cidadãos na nossa fronteira e que isso tem de acabar. Um país que não controla a suas fronteiras não consegue sobreviver, principalmente com o que se passa actualmente.

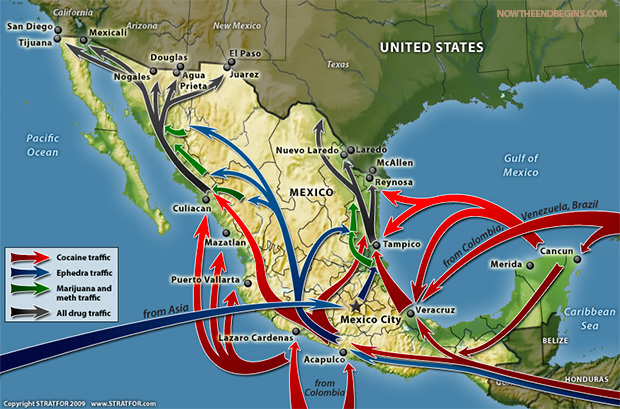

O que eu disse é simplesmente uma questão de bom senso. Falo com guardas fronteiriços e eles dizem-nos quem é que estamos a deixar atravessar a nossa fronteira. Os países que nos ficam a sul não estão a enviar os seus melhores cidadãos. As pessoas más não vêm só do México. Vêm de toda a América Central e do Sul e vêm provavelmente - provavelmente - do Médio Oriente. Deixem-me que acrescente agora: permitir que dezenas de milhares de refugiados sírios entrem pela nossa porta irá seguramente trazer muitos problemas. Porém, não saberemos a sua gravidade, porque não temos qualquer protecção e não temos qualquer competência. Não sabemos o que se está a passar. Isso tem de parar e tem de parar já.

Mais tarde, durante o anúncio da minha candidatura, acrescentei: "Construiria um grande muro e não há ninguém melhor do que eu a construir muros, nisso podem acreditar, e construí-lo-ei sem gastar muito dinheiro. Construirei um grande muro na nossa fronteira meridional. E farei o México pagar esse muro. Podem escrever essas palavras". Falei durante algum tempo nesse dia. Cobri praticamente todos os problemas que o nosso país enfrenta. Mas o que é que os meios de comunicação social disseram sobre esse discurso? "Trump é anti-imigração". "Trump chama violadores aos imigrantes". "Trump vai entrar em guerra com o México". Querem saber porque é que não estamos a resolver os nossos problemas? Porque é que nada muda? É porque não estamos a enfrentar os problemas e a promover algum tipo de acção.

O fluxo de imigrantes ilegais que entram neste país é um dos problemas mais graves que enfrentamos. Isso está a matar-nos. Porém, até eu abordar essa questão no meu discurso, ninguém falava honestamente sobre o tema. E em vez de dizerem: "Trump tem razão e é melhor fazermos alguma coisa para travar a imigração ilegal neste momento, senão vamos perder o nosso país", disseram: "oh, que coisa horrível que Trump disse acerca das pessoas tão simpáticas que vivem a sul das nossas fronteiras. Espero que não fiquem chateados connosco por causa disso. Talvez ele peça desculpa". Eu compreendo porque é que isso aconteceu. É muito mais fácil criticarem-me a mim por ser directo do que é efectivamente admitirem que esta situação da imigração é um problema perigoso e depois arranjarem uma forma de o resolver.

Deixem que vos diga isto com toda a clareza: não sou contra a imigração.

A minha mãe emigrou para este país, vinda da Escócia, em 1918 e casou com o meu pai, cujos pais tinham vindo para cá da Alemanha em 1885. Os meus pais são duas das melhores pessoas que alguma vez existiram e foram milhões de pessoas como eles que tornaram este país tão maravilhoso e tão bem-sucedido.

Eu adoro a imigração.

Os imigrantes vêm para este país e querem trabalhar arduamente, querem ter sucesso, educar os seus filhos e participar do sonho americano. É uma bonita história. Consigo fechar os olhos e simplesmente imaginar o que os meus familiares devem ter pensado quando o barco em que seguiam passou pela Estátua da Liberdade a caminho de Nova Iorque e das suas novas vidas. E se pudessem ver os resultados dos seus riscos e dos seus sacrifícios! Como é que alguém pode não dar valor à coragem que essas pessoas tiveram de ter para deixarem as suas famílias e virem para cá?

Aquilo que não adoro é o conceito de imigração ilegal.

Não é justo para todas as outras pessoas, incluindo as pessoas que esperam numa fila há anos para entrarem legalmente no nosso país. E o fluxo de imigrantes ilegais que atravessam as nossas fronteiras tornou-se um problema perigoso. Nós não protegemos as nossas fronteiras. Não sabemos quem cá está, mas aposto que os países de onde essas pessoas vieram sabem que eles saíram de lá. Contudo, esses governos não fazem nada para nos ajudar. Estima-se que existam 11 milhões de imigrantes ilegais na América, mas o facto é que ninguém sabe quantos realmente são. Não temos qualquer forma de os monitorar.

Aquilo que efectivamente sabemos é que alguns desses imigrantes são uma fonte de criminalidade real. Em 2011, a Government Accountability Office [Agência de Prestação de Contas do Governo dos EUA] divulgou que três milhões de detenções seriam atribuíveis à população estrangeira encarcerada, incluindo dezenas de milhares de criminosos violentos. Havia 351 000 estrangeiros ilegais nas nossas prisões; esse número não inclui o crime de atravessar as nossas fronteiras. Simplesmente manter essas pessoas na prisão custa-nos mais de mil milhões de dólares por ano.

Compreendo que a grande maioria dos imigrantes ilegais seja formada por indivíduos honestos, decentes, trabalhadores, que vieram para cá para melhorar as suas vidas e as vidas dos seus filhos. A América é cheia de promessas, e que pessoa honesta não gostaria de vir para cá e tentar construir uma vida melhor para si e para os seus filhos? Porém, a imigração ilegal é um problema que tem de ser enfrentado pelo governo dos Estados Unidos, que, por sua vez, tem de confrontar outros países. Sinto tanta pena desses indivíduos quanto qualquer outra pessoa. As condições em alguns dos países de onde vêm são deploráveis.

Todavia, a imigração ilegal tem de parar. Um país que não consegue proteger as suas fronteiras não é um país. Somos o único país no mundo cujo sistema de imigração coloca as necessidades das outras nações à frente das suas próprias necessidades.

Há uma palavra para descrever as pessoas que fazem isso: tolas.

Tenho um grande respeito pelo povo do México. As pessoas têm garra. Já estive envolvido em negócios com empresários mexicanos. Porém, esses empresários não são as pessoas que o governo mexicano nos envia. Há muita gente que já se esqueceu do Êxodo de Mariel. Em 1980, Fidel Castro disse ao povo cubano que quem quisesse abandonar Cuba era livre para o fazer. O presidente Carter abriu as nossas fronteiras a todos os que quisessem vir para cá. Mas Castro foi mais esperto do que ele. Esvaziou as prisões e os manicómios de Cuba e mandou os seus piores problemas para cá. Livrou-se das piores pessoas que havia naquele país e nós é que ficámos com a batata quente nas mãos. Vieram para cá mais de 125 000 cubanos e, apesar de terem vindo muitas e muitas boas pessoas, alguns indivíduos eram criminosos ou tinham problemas mentais. Mais de 30 depois, ainda estamos a lidar com esse problema.

Será que alguém acredita que o governo mexicano - na verdade, todos os governos da América Central e do Sul - não percebeu essa mensagem? O governo mexicano já publicou panfletos a explicar como é que se emigra ilegalmente para os Estados Unidos. O que só prova o que tenho vindo a dizer: não estamos aqui a falar de alguns indivíduos que procuram melhores condições de vida; trata-se de governos estrangeiros que se portam mal e de os nossos próprios políticos de carreira e os nossos "líderes" não fazerem o seu trabalho.

E quem é que pode culpar esses governos estrangeiros? É uma óptima forma que esses governos têm para se livrarem dos seus piores cidadãos sem pagarem absolutamente nada pelo seu mau comportamento. Em vez de enfiarem essas pessoas más nas prisões deles, enviam-nas para nós. Essa gente má está a trazer para cá o negócio da droga e outras actividades criminosas. Na verdade, alguns são mesmo violadores e, tal como vimos agora em São Francisco, alguns são assassinos. O homem que matou a tiro uma bela jovem tinha sido expulso do México cinco vezes. Devia lá ter ficado na prisão, mas, em vez disso, enviaram-no para cá.

O preço que estamos a pagar pela imigração ilegal é colossal.

Isso tem de acabar».

Donald J. Trump («GRANDE OUTRA VEZ. Como devolver a grandeza à América»).

«With all the storm and stress over President Trump’s temporary ban on citizens of several countries wishing to enter the United States, we may well wonder whether a country professing to be a land of the free has any moral justification for enforcing border controls. It is sometimes argued that international borders are artificial and unjustifiable limitations on one of the most fundamental of human rights, the right to freedom of movement. But are they?

Just as a perfect world populated by angelic beings would have no need of earthly government, as James Madison once observed, so too would such a perfect world have no need of international barriers. Were we all without sin, there would be no moral basis for preventing the absolute freedom of movement, such that people could choose to live in whatever climate or environment suited them, whether mountain or prairie, seacoast or tundra, city or village.

But the world we now live in does not remotely resemble such a paradise. Just as the task of the American Founders was to find the best type of government that humans in their fallible, fallen state could sustain, so the ever-changing boundaries and rules for international travel and commerce - not to mention immigration and naturalization - reflect an ongoing effort to adapt the worldwide system of sovereign nations to best suit the cultural and political realities of the human race.

When the United States of America was founded, it took shape not just as a collection of laws, magistracies, and jurisdictions. It also had, and still has - like every other country in the world - a distinct culture that underpins our entire political and legal system. In other words, the laws that we have protecting rights such as freedom of religion and of speech and the right to bear arms are in the first instance the product of a culture whose roots draw their sustenance from thousands of years of Judeo-Christian and classical culture. For instance, while there are many differences between our culture and that of ancient Rome, we share Roman assumptions about the need for order, about the paramountcy of the law, about military virtue, and so forth. While the world of Moses and the early Israelites in the desert seems mostly alien to us, the commandments that they received from their God are not. From more recent Christian culture, we derive our assumptions about the primacy of free will and individual liberty; for Americans, the notion of all-superintending Fate, so popular among ancient Greco-Romans and modern Asians alike, is inimical to liberty, which requires both individual choice and responsibility.

There remain, of course, many other cultures besides our own. Some of them are older than Western culture - much older. Chinese and Indian cultures probably stretch back, in something resembling recognizable form, to several thousand years before the “West” was even thought of. Others, such as Islamic culture in the Middle East, are younger. But many of these cultures have powerful elements, not easily set aside by those who espouse them, that are in direct contradiction to core Western values.

For example, in Islamic culture, abandonment of the religion of the faithful is unthinkable, and punishable by death. This means that large numbers of Muslims are particularly opaque to the influence of foreign culture - and, more often than not, to benefits, such as equality of the sexes and individual liberty - offered by Western society.

Nor are such cultural clashes a novel issue. Alexander Hamilton, routinely invoked as the Founding Father whose vision most accurately aligned with what America has in fact become, is seldom consulted nowadays on the matter of immigration. Yet Hamilton, writing some years after independence, in 1802, was no fan of unrestricted immigration - an opinion decidedly out of step with modern multiculturalism. In a time when constitutional limits on government power were still for the most part scrupulously observed, Hamilton understood clearly the potential for alien cultures to change our own commitment to republican principles:

The safety of a republic depends essentially on the energy of a common National sentiment; on a uniformity of principles and habits; on the exemption of the citizens from foreign bias, and prejudice; and on that love of country which will almost invariably be found to be closely connected with birth, education and family.... Foreigners will generally be apt to bring with them attachments to the persons they have left behind; to the country of their nativity, and to its particular customs and manners. They will also entertain opinions on government congenial with those under which they have lived, or if they should be led hither from a preference to ours, how extremely unlikely is it that they will bring with them that temperate love of liberty, so essential to real republicanism? There may as to particular individuals, and at particular times, be occasional exceptions to these remarks, yet such is the general rule.... By what has been said, it is not meant to contend for a total prohibition of the right of citizenship to strangers.... But there is a wide difference between closing the door altogether and throwing it entirely open.... Some reasonable term ought to be allowed to enable aliens to get rid of foreign and acquire American attachments; to learn the principles and imbibe the spirit of our government; and to admit of at least a probability of their feeling a real interest in our affairs. A residence of at least five years ought to be required.... To admit foreigners indiscriminately to the rights of citizens, the moment they put foot in our country ... would be nothing less, than to admit the Grecian Horse into the Citadel of our Liberty and Sovereignty.

In sum, all countries have the right to control their borders, not only to restrain criminal activity, but also to safeguard their culture - especially if that culture upholds liberty and limited government».

Charles Scaliger («Should Nations Enforce National Borders?», in The New American, 21 March 2017).

United States of Europe

This article first appeared in the April 10, 1989 print edition of The New American

, providing seminal research that exposed the hidden agenda behind the developing European Economic Community. Not only did Mr. Jasper present crucially important information that was almost completely unknown at that time, even to generally well-informed Americans and Europeans, concerning the individuals and organizations pushing for European "integration," but he also accurately "projected the lines" — decades ahead of other analysts — presciently sounding the warning that false appeals to free market rhetoric were masking a plan for socialism and the destruction of personal liberty and national independence for the nations of Europe. With the White House and Congress now considering action on legislation for a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), to further entangle the United States with the European Union, this article from 24 years ago is more relevant than ever. — The Editor

1992. In the minds of most Americans, the year probably holds no significance beyond being another presidential election year, and the occasion of another Olympic Games. Increasingly though, Americans will begin to realize that fast-approaching year carries far greater political and economic significance.

Readers of business publications and economic journals have already seen a surge of articles heralding 1992 as the year of the "European market," as a benchmark period during which a host of trade barriers and other restrictions among the 12 countries of the European Community, or Common Market, will come tumbling down. Nineteen ninety-two is the year that the Single European Act (SEA) goes into effect. That act, agreed to by the 12 member states in 1986, calls for the establishment of "an area without internal frontiers, in which the free movement of goods, persons, services, and capital is ensured."

"With progress toward a single market, European industry will be able to achieve greater economies of scale," said Deputy Secretary of the Treasury M. Peter McPherson in an address to the Institute for International Economics in 1988. "The demands of competition will spur technological innovation and greater productivity. The program can help stimulate growth and employment, reduce consumer prices, and raise standards of living throughout Europe." McPherson added: "The force that will drive this transformation is opportunity -- the opportunity to compete in a larger and freer marketplace. European manufacturers today face a myriad of obstacles to trade with other member states, ranging from profound differences in regulatory and tax systems to varying national technical standards. For example, an electronics company in the Netherlands now has to meet 12 separate sets of technical standards to be able to sell throughout the Community."

Free Market Rhetoric

Dr. Ron Paul, the former Republican congressman from Texas and recent candidate for U.S. President on the Libertarian Party ticket, is one of those who sees that approaching milestone very differently. Long an ardent champion of free market economics, he warns that the movement toward European "union" and "integration" is a statist scheme cloaked in free-market rhetoric that is likely to "produce a monster." "International statists have long dreamed of a world currency and a world central bank," wrote Dr. Paul in the October 1988 issue of

The Free Market, published by the Ludwig Von Mises Institute. "Now it looks as if their dream may come true."

In his essay, "The Coming World Central Bank," Paul commented:

European governments have targeted 1992 for abolishing individual European currencies and replacing them with the European Currency Unit, the Ecu. Next they plan to set up a European central bank. The next step is the merger of the Federal Reserve, the European central bank and the Bank of Japan into one world central bank....

The European central bank (ECB) will be modeled after the Federal Reserve. Like the Fed in 1913, it will have the institutional appearance of decentralization, but also like the Fed it will be run by a cartel of big bankers in collusion with politicians at the expense of the public.

Of course, the much-touted "free-market reforms" are really only bait laid out to entice Europeans into the trap of an (eventually) all-powerful supranational government. Many of the coming reforms are laudable in and of themselves and will indeed bring genuine market benefits to the people of Common Market countries. The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), for instance, will lose its monopoly on television broadcasting, which will both allow viewers in the U.K. access to foreign programming and encourage the growth of domestic private sector television stations. Financial services will be revolutionized by the invigorating winds of competition, as banks and corporations are given freer rein to operate across national borders. Powerful national unions will lose their strangleholds on vital economic sectors. Air travel should become more affordable as the European air carrier industry is opened to free competition.

Short-Lived Reforms

However, these reforms, if they do come about, will likely be short-lived. The reason is that the Single European Act has committed the 12 member nations to increased political and monetary integration, meaning an increased shift of sovereign powers from national capitals to the Common Market institutions in Brussels, Luxembourg, and Strasbourg. These institutions are controlled by Keynesian interventionists, socialists, and internationalists.

In the European Parliament, where the 518 elected deputies sit in political, not national, groupings, the Socialist Group is by far the largest force, with 165 members. It is followed by the European People's Party Group (114 members), the European Democratic Group (66 members), the Communist and Allies Group (48 members), the Liberal Democratic and Reformist Group (44 members), the Group of the European Democratic Alliance (29 members), the Group of the European Right (16 members), and the Non-Attached (15).

The makeup of the European Community Commission and the Council of Ministers, the institutions with the real legislative and executive power, is no better. They are dominated by men like Commission President Jacques Delors, a former French Finance Minister who is leading the push for a European central bank, as well as other assaults on national sovereignty; Commissioner Willy de Clercq, a member of David Rockefeller's Trilateral Commission and, as the Common Market's trade minister, a leading proponent of Western financial and technological assistance to the Communist bloc; Commissioner Karl-Heinz Narjes, who also is a Trilateralist; Italian Socialist Carlo Ripa di Meana, the Commissioner now in charge of "environment and nuclear security"; and German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, who urges Europeans "to take Mr. Gorbachev seriously, to take him at his word," passes out "I like Gorby" buttons, and champions unilateral Western disarmament.

Formally known as the European Community, the Common Market is the direct creation of individuals and organizations that have been involved in various utopian and conspiratorial schemes to establish a world government, a "New World Order," for the better part of this century.

In the aftermath of World War I, world leaders met in Paris in 1919 to settle war claims, redraw the face of Europe, and hammer out what became the Treaty of Versailles. President Woodrow Wilson came to the Peace Conference with his famous "fourteen points," the spring-board that helped launch the League of Nations. Among those who accompanied Wilson to the Conference were his ever-present advisor and mentor Colonel Edward M. House and three young men who were destined to play key roles in the forming of a United Europe: John Foster Dulles, Allen W. Dulles, and Christian A. Herter -- Mr. Wilson's "Brain Trust."

|

Edward Mandell House

|

According to Wilson and House biographers, it was the mysterious Colonel House (an advocate of "Socialism as dreamed of by Karl Marx") who actually drew up the "fourteen points," drafted the Covenant of the League of Nations, assembled the "Brain Trust," and imbued Wilson with the vision of a socialist one-world government. Be that as it may, the Wilson-House dream of the League as a nascent world superstate came to naught when the U.S. Senate rejected the treaty as a dangerous assault on our Constitution and our national sovereignty.

The Council on Foreign Relations

Realizing that the American public and the U.S. Congress were not sufficiently "internationalist-minded," and that such "outdated" concepts as the nation-state, patriotism, inalienable personal rights, constitutionally-limited government, and a foreign policy with "no entangling alliances" were still widely and tenaciously adhered to, Colonel House and his fellow internationalists set about to change the American consciousness. In 1921 they established the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) in New York as a "study group" on foreign relations. Drawing together influential one-world-minded men from high finance, industry, the news media, politics, and academe, the CFR soon became the dominant force directing American foreign policy and promoting centralized government planning and socialism at home and abroad. Men like Rockefeller, Morgan, Aldrich, Baruch, Warburg, and Lippmann provided financial backing, prestige, and political clout to the new organization dedicated to building "international order."